The Sorrowful Mysteries

Recently while praying the Sorrowful Mysteries of the Rosary (the Sorrowful Mysteries include: the Agony in the Garden, the Scourging at the Pillar, the Crowning with Thorns, the Carrying of the Cross, and the Crucifixion), when I came to the Crucifixion, I suddenly felt like I was going to throw up. I’ve prayed it so many times, but this time it literally made me sick. And it hit me—this isn’t the Mystery of Death. No, this is something else altogether.

The Sorrowful Mysteries aren’t about pain and death, not really. They’re about cruel human caricatures, exaggerations, of pain and death. We all feel pain and we all die. That’s no great sorrow—it’s simply the way of things. What’s truly sorrowful is that human beings wield, inflict, and extend pain and death for the sake of power and domination. That’s what’s on display in the Sorrowful Mysteries—our own tragic, brutal, and unnecessary violence.

First, we find ourselves with Jesus in the garden, where he faces the agony of impossible decisions—making a choice that is not asked of him by nature, but rather by violent human beings and violent human systems. He is then abused, beaten, mocked, and finally murdered. The one fleeting moment of beauty, of kindness in these mysteries, is in the Carrying of the Cross—when Simon of Cyrene steps in, not to further Jesus’ pain, but to help him shoulder the burden. But even in this fleeting kindness, we see the way systems of domination simply pull others into the orbit of their violence.

There is another rosary that is waiting to be prayed; one that passes from the Joyful Mysteries, through the natural mysteries of pain and diminishment, loss and death, on to the Glorious Mysteries of integration, transformation, and renewal. That rosary is for a future humanity that has left behind the way of violence. We, however, are still confronted—still confront ourselves—with the Sorrowful Mysteries. Perhaps we will always need to pray them so as never to forget.

Implicit in these mysteries is the account of Jesus’ trial, in which the Gospels tell us that Pontius Pilate set before the crowds two men, both of them Jesuses—Jesus Barabbas and Jesus “called the Messiah.” Then the people—we—are allowed to choose, to release, one or the other.

Jesus Barabbas, we learn from Mark’s account, was a rebel who committed murder during a violent insurrection against Rome (and don’t get me wrong, Rome deserved it). Jesus “the Messiah” modeled a different way, a path of nonviolent resistance. The people choose Jesus Barabbas. That choice then leads the other Jesus through the Sorrowful Mysteries, which unmask the normalcy of civilization for the cruelty and violence that it actually is.

By the time the Gospels were written, between 70 and 100 AD, the Jerusalem Temple had been destroyed, razed to the ground, during a bloody seven-year Jewish-Roman War that was set off, in large part, by violent revolutionaries. It’s almost as if the Gospel authors, writing decades after the life of Jesus, are now able to look back and see the path that history has taken, and so take us back to the moment when we chose violence over nonviolence, and they invite us to choose again. Walk away from all of this, they plead—the Sorrowful Mysteries plead.

The history of our choosing isn’t so great. Currently, over half of all federal spending in the United States goes to our military—that is, to maintaining the violent normalcy of civilization. 738 billion dollars of our 2020 budget was set aside for military purposes, while only 64 billion went to education. Again and again, the way of violence, of power-over, and the way of nonviolence, of solidarity-with, are set before us. Again and again humanity has said, “Give us Barabbas!”

It’s telling that the name “Bar-Abbas” seems to be a symbolic name; it literally means “son of the father”—you could translate this colloquially as “a chip off the old block.” Barabbas is a son of the ways of our fathers, a “son of the patriarchy,” a “son of the normalcy of violence.” But the other Jesus speaks of a different Abba; not the ways of our human fathers, but of “our Abba [Amma] in heaven” who “causes the sun to shine on the evil and the good, and sends rain on the just and the unjust alike.” The Gospels call this Jesus “Jesus bar Miriam,” Jesus the son of Mary, the son of his Mother.

Barabbas, the son of the father, is etymologically the same word as our English word “patriot” from the Greek patriotes, which means “of one’s father.” It is no mistake that patriotism and patriarchy are related words. And it is not a coincidence that Hitler referred to Germany as “the Fatherland.” We see all around us today the rise of the kind of virulent, patriarchal nationalism that leads always to violence, walls, and borders. We saw it on bold and frightening display during the January 6th riot at the U. S. Capitol. “Give us Bar-Abbas!”

But we see in Jesus Bar-Miriam a different way—the way of his Mother, who sings in her Magnificat of the mighty pulled down from their thrones and the lowly lifted up. The way not of our earthly fathers who fought wars and set up the borders of their kingdoms, but of our mothers, and of our “heavenly” Abba/Amma whose kin-dom has no borders, and whose mode of “battle” looks like a gentle soul dying in unjudging love on a cross. A cross that was never necessary.

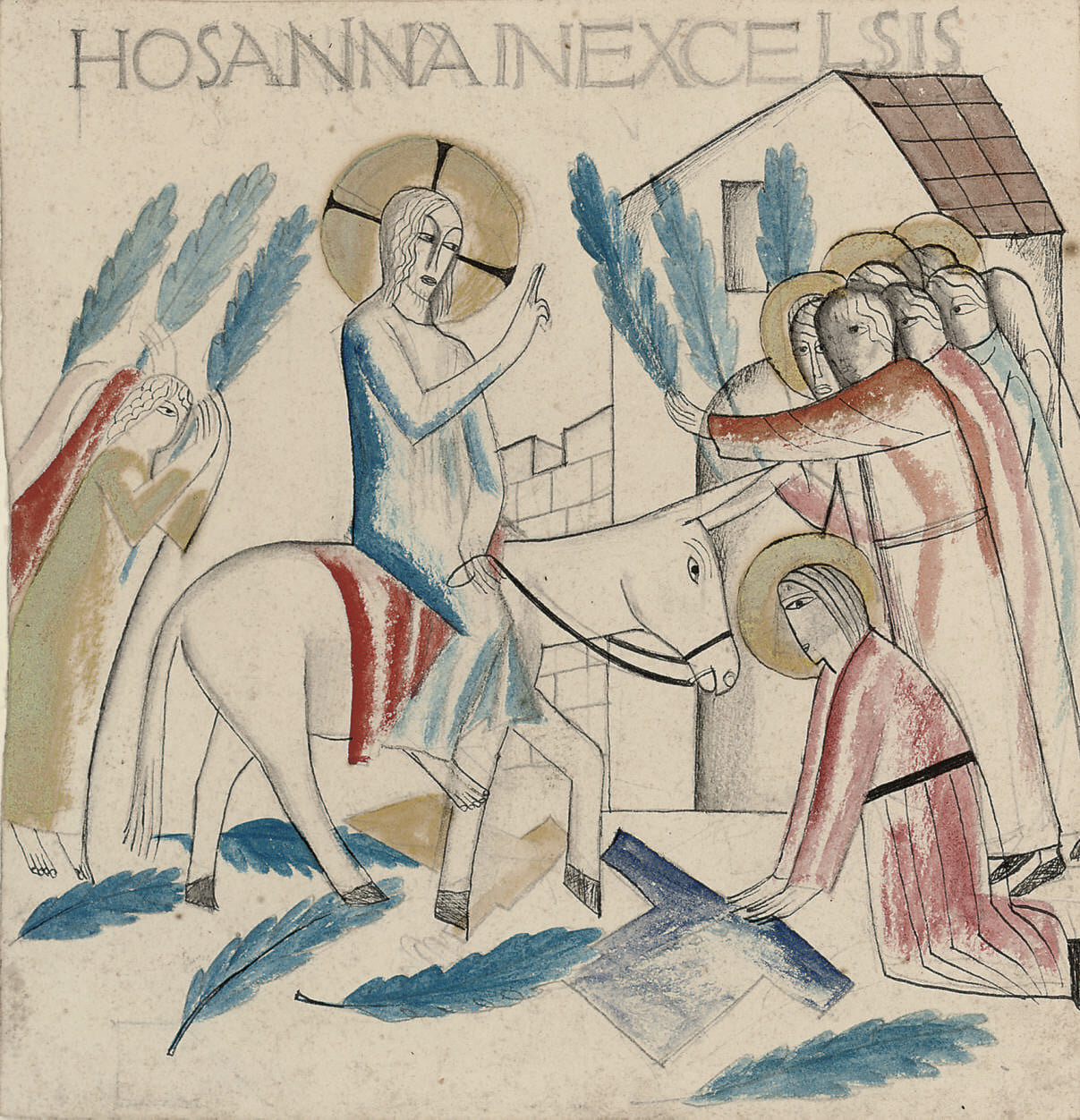

In the lead-up to the passage through the Sorrowful Mysteries, when Jesus rides a donkey into Jerusalem as peasants welcome him with leafy branches, he was, in fact, staging a counter-procession to one that happened every year on that same day. On the opposite side of the city, the Roman governor rode into Jerusalem on a warhorse with full imperial pomp—armor, weapons, banners, soldiers—a military procession, set at the start of the week of Passover, to remind the Jewish people who was in charge. It was the violent dominance of patriarchy on full display.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the city, Jesus bar Miriam rode in, not on a high warhorse, but a lowly donkey. Legend says that this was the same donkey that his mother once rode to Bethlehem, the same donkey that carried her when she fled as a refugee into Egypt. It’s not impossible; Jesus was around 30 when he died, and the average lifespan of a donkey is about 30 years, although a well-loved one might live even to 50. The text tells us that Jesus knew where the donkey was tied, and that if anyone said anything to the disciples when they went to retrieve it that they should simply say that he, Jesus, was in need of it and that it would be sent immediately.

Was it because he already knew this donkey? That the family who cared for it knew his family? That it had once carried him while he was in the womb and that it would now carry him one final time? It’s a beautiful bookend to the story. Here, Jesus the son of Mary proclaims the kin-dom of God, not by climbing onto the high warhorse of our fathers, but by sitting on the back of the lowly donkey of his Mother.

A warhorse is meant to lift you up off the earth, to make you less vulnerable to attack; a donkey keeps you close to the ground. Do we follow Jesus Barabbas, the son of the father, a chip off the old patriarchal block, or Jesus bar Miriam, the son of the Mother, riding on her lowly donkey? The way of Jesus bar Miriam stays close to the Earth, listens to the donkeys and the trees, the lilies of the field and the birds of the air. In the 6th century, St. Maximus the Confessor wrote of Mary that “Wherever she went, she consecrated the earth with her footsteps.”

In his book The Return of the Mother, the contemporary mystic Andrew Harvey tells of a dream he once had. In the dream, he is searching for the Mother; he looks in churches and ashrams, but wherever he goes, he can’t find her. Finally, exhausted, he comes to an old farmhouse where there’s “a small ragged field with only a little grass in it and an old donkey who stood flicking the flies off his back with his tail.”

He writes, “Suddenly, I felt calm. I had stopped looking for anything or anyone and all I wanted to do was sit down. I found a small rock and as I was about to sit I heard the creak of a door. I looked up. The door of the small farmhouse was opening. There, in the half-light, stood an old haggard peasant woman in black. She stopped and looked at me a long time and until I die I will never forget the intimacy, tenderness, and sober absolute compassion of that look. It was her, alone and simple and poor and one with all nature and all beings and an old woman.

“She lowered her head and walked a little crookedly and unsteadily into the light. She was carrying a pail of water in her right hand and she walked slowly over to the old donkey, to give it a drink. I thought as she held the half-blind face of the donkey to her own and closed her eyes, ‘Perhaps it was on this donkey that her son rode into Jerusalem.’ I awoke and wrote down the words that I heard inwardly: ‘Know me in my simplicity and awake to my love and my justice.’”

May we awaken from the nightmare that is the Sorrowful Mysteries. May we return to the moment of our choosing, and choose differently this time, choose to walk away from violence, from domination, from the way of Bar-Abbas, and embrace instead the way of Bar-Miriam, the Way of the Mother, the way of gentleness, simplicity, justice, and love.